Imagine, if you will, a MotoGP race where Peco Bagnaia crashes, and kills Marc Marquez in the process. Or imagine a MotoGP race where Valentino Rossi high-sides and is killed, while his bike smashes into Jorge Lorenzo and kills him as well.

It doesn’t bear thinking about, does it? And while we all know MotoGP riders risk their lives on every lap of every race, today’s safety measures have come a long way. So while the aforementioned scenarios are not impossible, they are highly improbable.

But just such a tragedy occurred not all that long ago, in 1973, and ended the lives of two of our sport’s greatest riders – Jarno Sarrinen and Renzo Pasolini.

The incident, which happened at Monza on the first lap of the 250cc Nations Grand Prix, has been written about many times. It is seared forever into the memories of former racers and officials, and there would not be a single Italian racer who would not be aware of the Monza tragedy.

How and why it happened has been debated many times over the years – but an air of mystery still surrounds the events more than half a century later.

One man went to his grave carrying responsibility for the crash. Walter Villa, who was racing a Benelli in the 350 class that preceded the 250 race, understood his bike had dumped oil on the track at Turn One, known as Curva Grande, the Grand Curve (also known simply as Il Curvone, or The Curve) where the incident occurred in the 250 race.

Walter was publicly exonerated only in 1993, after he had passed, when the Italian magazine, Tuttomotto, finally published the results of the investigation 20 years after the tragedy.

That investigation, instigated by the Italian government and headed by Ferrari technical director, Sandro Colombo, found the culprit was Pasolini’s Aermacchi Harley-Davidson. Apparently, its shitty water-cooling system had malfunctioned and caused Pasolini’s right-hand cylinder to seize.

But doubt has been cast on that finding by Don Emde in a story the hugely-respected American magazine, Cycle World, ran in 2023 as part of a Pasolini tribute.

Don Emde is a former Daytona winner, who has been very interested in the Monza tragedy. He does not dispute the seized piston finding. He just questions the timing of the seizure.

“It depends on when it seized,” Don said to Cycle World. “Did the piston seizure cause the crash? Or is it possible that the motorcycle seized afterwards, which can also happen. If a machine lands on its right side, the throttle can get stuck in the ground, sometimes revving it into wide-open, which can certainly cause an engine seizure.”

Ultimately, this question may never be answered. But what we do know is this double-fatality changed the face of motorcycle racing from that day on.

This is what we know happened on that day…

Renzo Pasolini had raced against Agostini in the 350cc class earlier that day. By all accounts it was a great race, and Renzo briefly had the goods on Giacomo, before overcooking a bend riding into a paddock. And we can actually read a rather wonderful race report from Carlo Perelli, which ran in Cycle World on 1 September, 1973…

“Run in the early afternoon, the 350 race was one of those the enthusiasts will always remember. Paso had been the fastest in practice with the new water-cooled Harley Davidson but owing to one of his not unusual bad starts he was only 12th at the end of Lap 1. In the meantime, the lead was ferociously contested by Agostini (MV Four), Walter Villa (Benelli Four) and Lansivuori (Yamaha); Ago’s teammate. Read, also on a Four, had ignition trouble and had to retire. The leading trio was offering a super-show, with Lansivuori sometimes putting his wheel ahead of Ago’s, but after a few laps, all eyes and hearts were on Paso, quickly gaining ground. At the 13th of 24 laps, after setting a new record lap (for the 1st time over 124 mph with a 350!), Renzo was right behind Ago who had widened a slight gap over Lansivuori and Villa. But after one more lap the crowd was in delirium: Paso was leading! Powerful yet quiet in his action, Paso seemed sure of the win. Ago, on the other hand, was riding at the very limit. With only three laps to go, however, yet another stroke of ill luck awaited Paso. In braking for the parabolic bend, his engine had a slight seizing, and he went straight in the meadow, without crashing. Success at record speed was once again Ago’s, with Lansivuori 2nd. Walter Villa was dramatically slowed in the last three laps by oil losses. He finished 5th behind Andersson and Dodds.”

So, pretty much smiles all around. Ago even remembered how Renzo looked back at him as he passed him in that race.

But now there was oil on the track from Villa’s Benelli. The riders demanded it be cleaned up, and asked the 250cc race be postponed until that happened.

The officials didn’t want to do that because it would impact on the schedule. They threatened to call the cops if the racers didn’t piss off and stop bothering them about such trivial shit as oil on the super-fast Turn One. A vague attempt was then made to clean up the spill, but it was a bodgey job by all accounts.

According to our mate, Carlo, who wrote the report for Cycle World quoted above, Turn One “is a very fast right-hander known as the ‘curvone’, at a speed of approximately 124mph (200km/h). This bend can be managed at about 142mph (228km/h), but of course the speed was down on Lap 1 because the “curvone” is not far from the start.

“The track there is narrow and runs in the wood. At the left it is sided by a guardrail, covered by a meagre line of straw-bales. There is strictly one line here for the rider in a hurry; otherwise, you have to slow down noticeably or get off…”

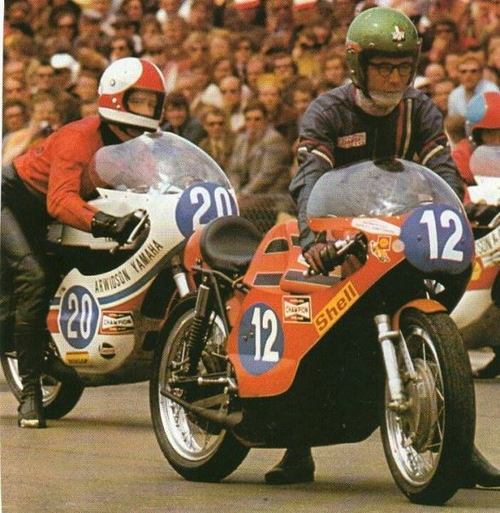

When the flag dropped, the front row, Saarinen, Kanaya, Pasolini, Lansivuori, and Braun had mixed starts. Saarinen and Pasolini muffed theirs and were overtaken by some of the blokes starting on row two – Lega, Villa, and Gallina – but it was Braun who was leading when the pack entered the Grand Curve. Pasolini was hard on his back wheel.

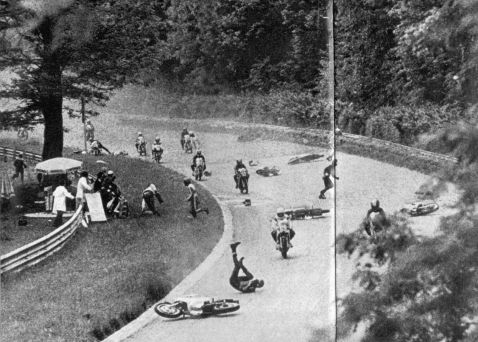

Then Pasolini’s back wheel stepped out – possibly because of the oil, possibly because of a rut in the pavement, possibly because his engine had seized, or possibly because of a combination of all three, or even something entirely different.

Renzo Pasolini was hurled into the Armco fence, while his bike became airborne and hit Saarinen in the head, tearing off his helmet. Lega and Gallina, who were on the same line as Saarinen, managed to avoid the accident, but Villa, Jansson, Mortimer, Palomo, Giansanti, Kanaya, and at least four others hit the ground. Fuel tanks ruptured and the haybales caught fire. The scene was instantly a blazing and chaotic catastrophe.

Most of the trailing riders managed to get through the inferno by pure luck, though not all. A total of 14 riders went down. Pasolini and Saarinen were both dead.

The race continued for two more laps. No warning flags were shown. It was later said the officials and marshals were “criminally slow” in getting to the scene, and the remaining racers had to weave their way through the carnage until they’d finally had enough, pulled into the pits, and the race was thus ended.

Mat Oxley wrote a piece on the Motorsport website, where he quotes British rider, and top privateer, Chas Mortimer, who remembers it like this:

“I was the third person that crashed,” says Mortimer, the only rider to have been victorious in 125, 250, 350 and 500 GPs and F750 races. “I killed Pasolini, actually. There’s a picture of me coming out of the flames with Pasolini lying right across the road and I ran straight into him.

“It was Pasolini and Saarinen and their bikes hitting the barriers and coming back onto the circuit that started it all, then the hay bales caught alight and it was just bloody carnage. I was about the only person that was able to walk away from it. Everyone else was stretchered away. I remember running over see Jarno – all his head had gone virtually – it was bloody horrendous… It was a bloody enormous accident, the biggest there’s ever been in Grand Prix racing.”

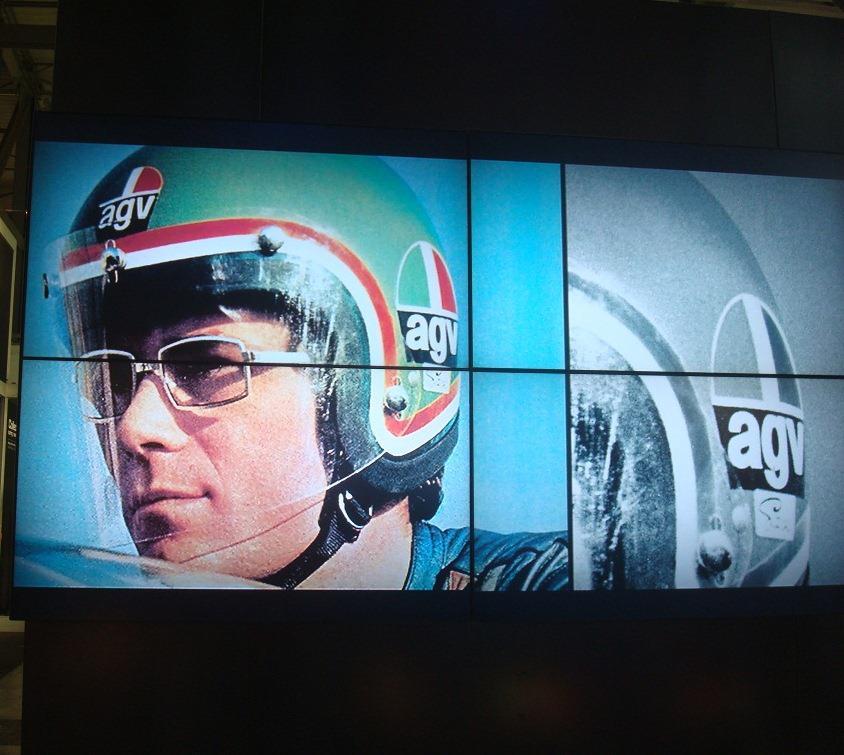

Renzo Pasolini was the most loved racer in Italy at the time of his death at the age of 34. More than 20,000 people attended his funeral. He raced in an open-faced helmet because he wore glasses and the full-face lids of the day would just cause them to fog up on him.

He was born in 1938 in the province of Rimini, on the Adriatic coast of Italy. His father, Massimo, was also an Italian motorcycle champion, and a young Renzo tried both boxing and motocross in his youth, before deciding he would road-race. His racing career was interrupted by two years of compulsive military service in the army, but he returned to racing at the age of 26, when he scored his first racing points, ironically, at the Nations Grand Prix at Monza in 1964.

He went on to race at the world’s greatest tracks – the Isle of Man, Assen, Daytona – often on brands like Benelli and Aermacchi, that weren’t as competitive as the MV Agustas ridden by Agostini, Read, and Hailwood. Nonetheless, he managed six Grand Prix victories in his 10-year-long career. The year before he died, he was beaten by one point to the 250cc World Championship by Jarno Saarinen.

“I ride,” he once said, for the pleasure of riding. And if I win, so much the better!”

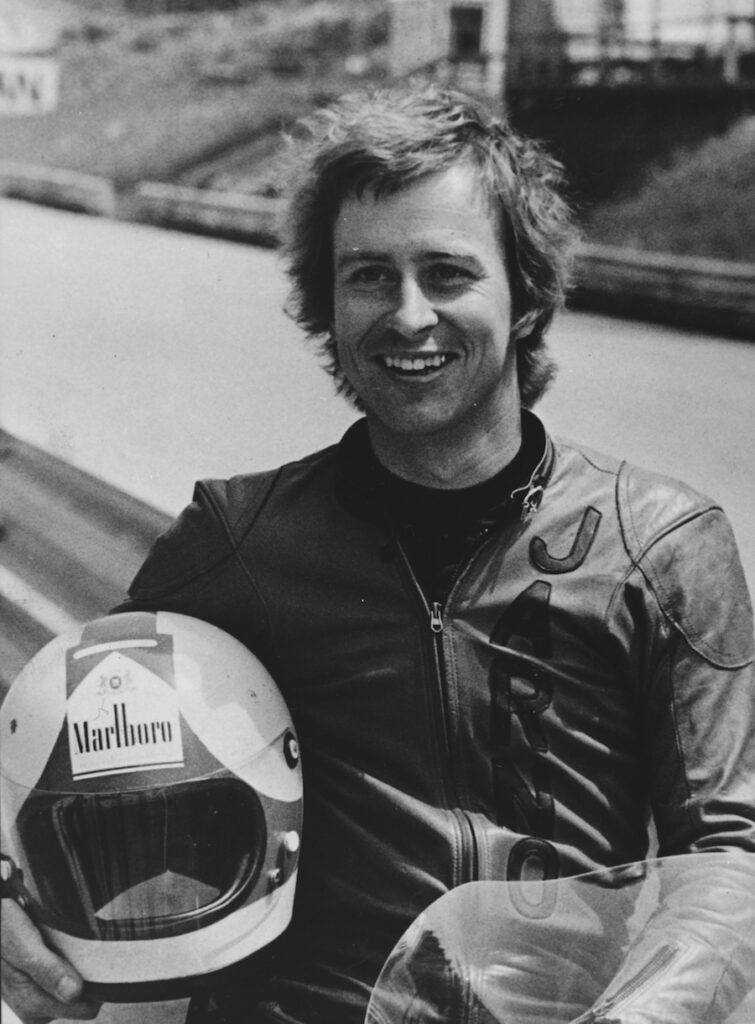

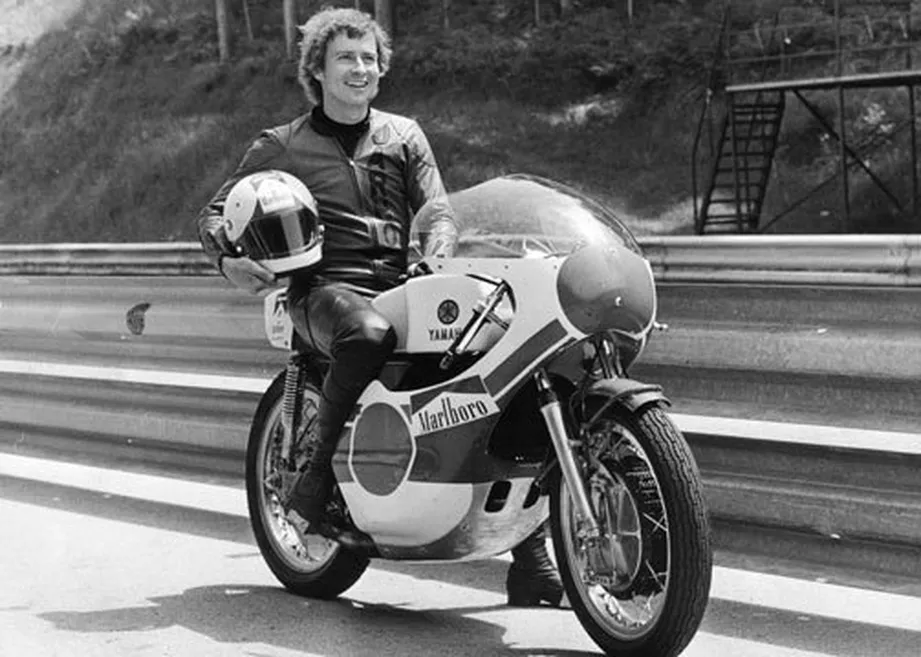

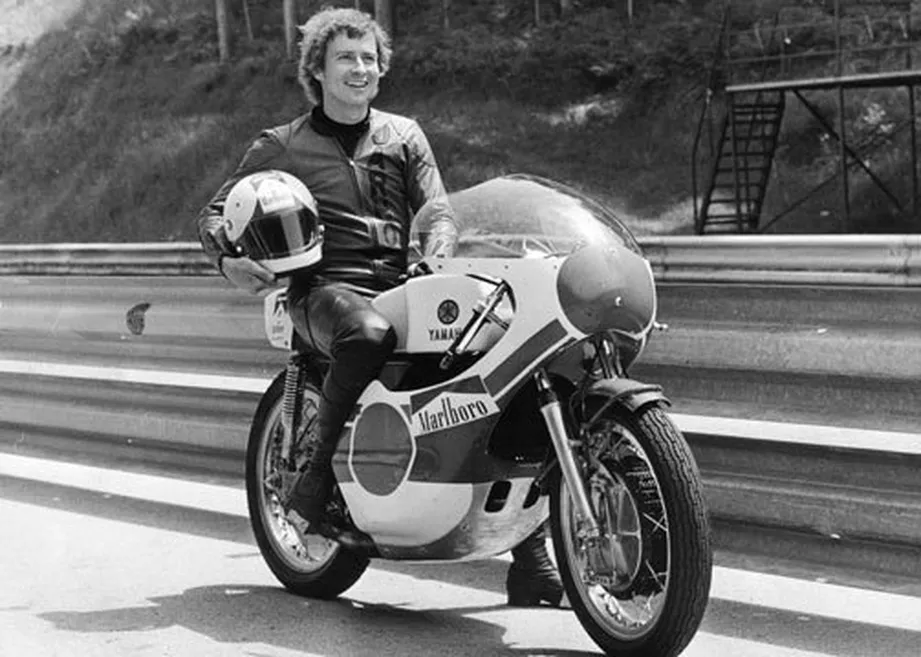

Jarno Saarinen, was a very different character, and considered to be one of the most talented and promising racers of his era. He remains the only Finn to have ever won a world motorcycle road-racing championship and was inducted into the FIM MotoGP Hall of Fame in 2009.

Jarno was born in Turku, Finland in 1945. At 15, he went to work as an apprentice mechanic and test-rider for Tunturi-Puch, a Finnish motorcycle factory which made bikes under licence for the Austrian Puch concern.

He made his racing debut in an ice-racer in 1961, where he came second in the national championship, but he raced speedway, grass-track, and road as well. He won the 1965 Finnish ice-racing national championship, and in 1968, he made his Grand Prix debut at the Finnish Grand Prix in Imatra on a 125cc Puch.

It was the big league. He came 11th, and was lapped three times by Bill Ivy and Phil Read. In those days, he was also his own mechanic, and in 1969 he won the Finnish 125 and 250cc national championship. People noticed his unique riding-style – chest above the tank, knee out, handlbars vertical, and rear tyre sliding like mad. Watching him race was a huge influence on young Kenny Roberts.

Jarno’s first full year in the 250cc World Championship was in 1970. He was still his own mechanic. He had also convinced three different bank managers to fund his racing by bullshitting them into thinking they were funding his education.

He finished fourth that year, despite missing the last three rounds of the season so he could complete his engineering degree.

The following year, Jarno was up against the reigning three-time 350cc champion, Giacomo Agostini. Jarno won his first race in Czechoslovakia. He then came second to Ago in Finland, and then won the Nations Grand Prix at Monza in Italy. That year, he finished third in the 250cc class and second behind Ago in the 350cc class.

The next year saw Jarno as Barry Sheene’s team-mate, both supporting Jan De Vries, as their team, Kreidler, waged a battle to the death with Derbi. Jarno came second that year behind De Vries, and secured Kreidler the championship.

Yamaha hired him in 1972. Jarno went on to win four of the last six 250 GPs in a season-long war with Renzo Pasolini and Rod Gould. That same year he finished second in the 350cc championship, again behind Ago.

For 1973, Benelli snapped him up to ride its 350 and 500cc bikes. He beat Ago in both classes at the Pesaro street circuit. Then Yamaha offered him a factory ride in the 250 and 500cc classes on its new YZR250 and YZR500. The year 1973 had started really well for Jarno.

He became the first European to win the Daytona 200. He did that on a production racer Yamaha TZ350. And when he came back to Europe, he flogged the field at the Imola 200, most of which were on bigger-capacity bikes.

And because in those days you could race lots of things in lots of championships, Jarno was again kicking arse in the Grand Prix. A double victory in the French GP – winning the 250cc race by more than 27 seconds, and then handing Phil Read his arse by 16 seconds in the 500cc class.

Jarno arrived at the fateful race in Monza leading both the 250cc championship and the 500cc championship. And Monza was a bastard of a circuit, lined with steel guardrails. They had been put there because car-racers started screaming they had to be installed after 15 spectators were killed when Wolgang Von Trips ploughed into them with his race car in 1961. Wolfgang also died.

Jarno complained about the guardrails when he arrived at the track. He was ignored.

The fallout from the Monza catastrophe was epic. Yamaha withdrew its factory team from the season. Lots of racers just stopped racing. Changes had to made, but they were slow in coming. More racers had to die before the organisers started to take rider safety seriously.

Less than two months later, on the same corner, three more riders were killed. Renzo Colombini, Renato Gatrucci, and Carlo Chionio, racing in the Junior Championship, lost their lives on 8 July, 1973.

The last motorcycle death at Curva Grande was in 1999. Marco Burnelli died when his 600cc Ducati went down in an Italian Supersport race.

In 2010, at the Monza round of the WSBK, Max Biaggi set the fastest ever motorcycle lap at the track on an Aprilia RSV4 1000F – 1:41.745.

In 2016 work was planned on a new Turn One, which would have bypassed the first chicane and the Curva Grande. But these plans were suspended due to the track being classified as “historic”.

MotoGP does not race at Monza anymore. Nor does the WSBK.

If you wish to see images of the accident, I warn you they are very confronting. But they are HERE IF YOU NEED TO SEE THEM